Bioplastic Series Interview

with Matthew Zamora, interviewed by

Christine Davis

What does the bioplastic series talk cover?

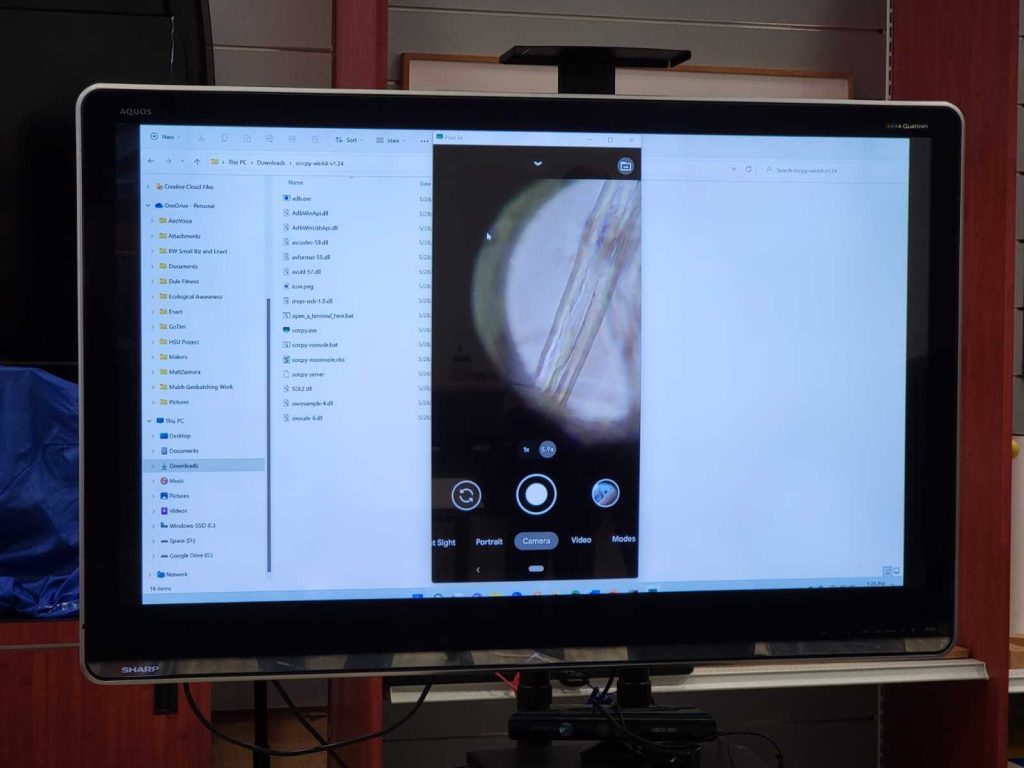

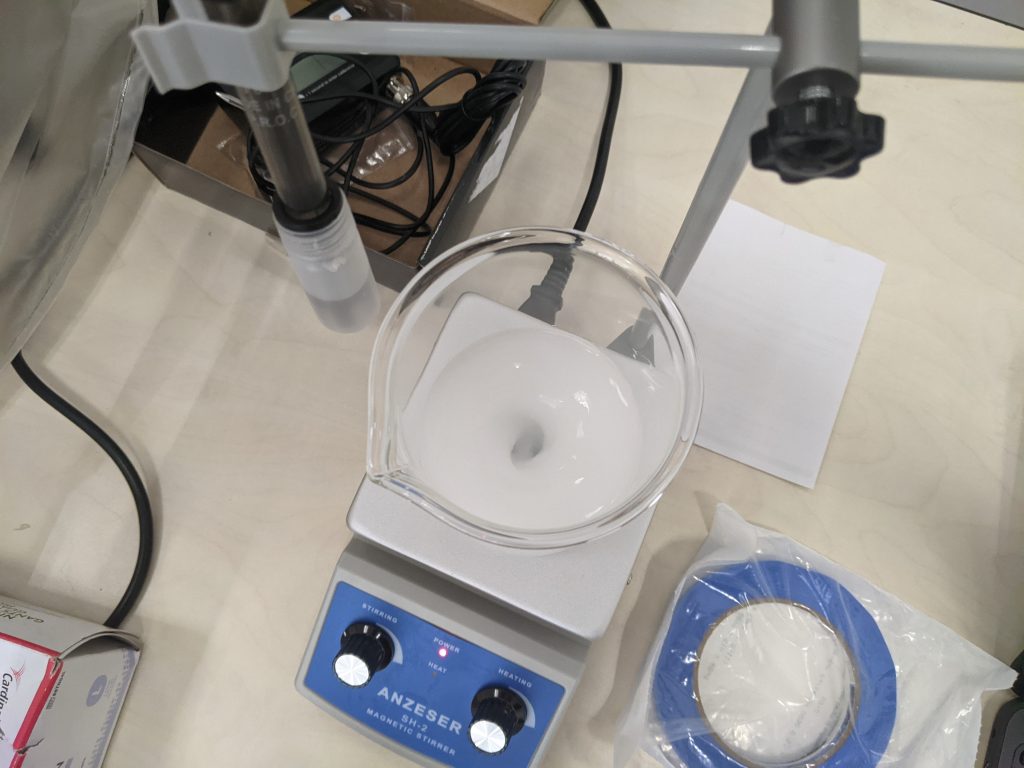

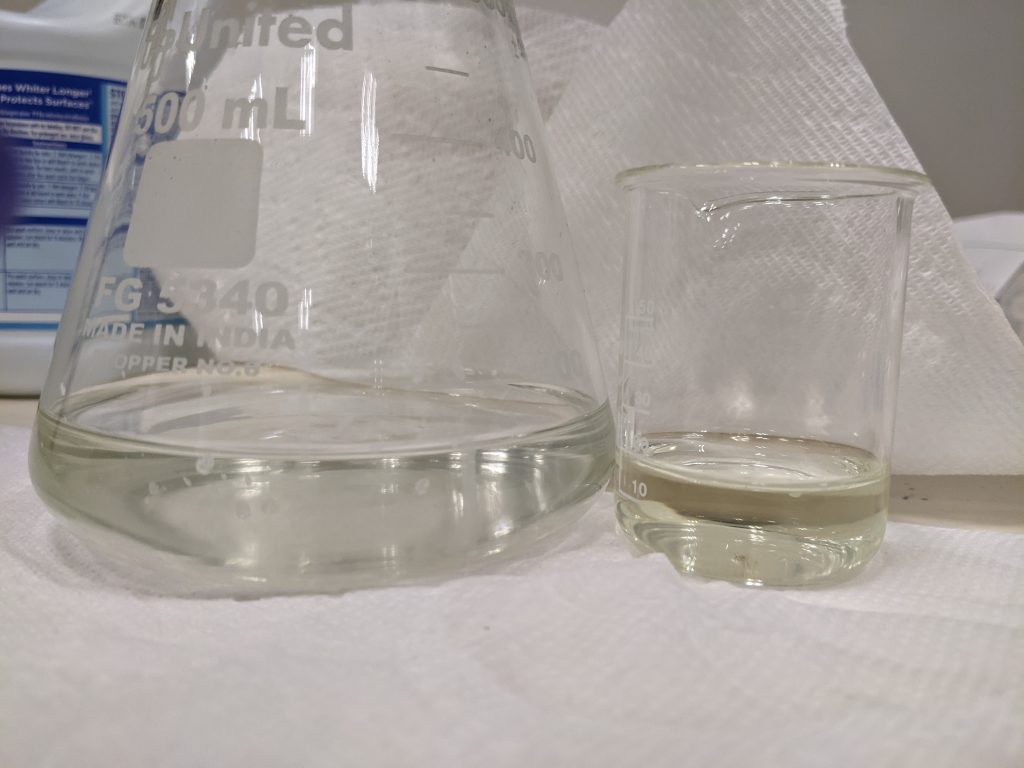

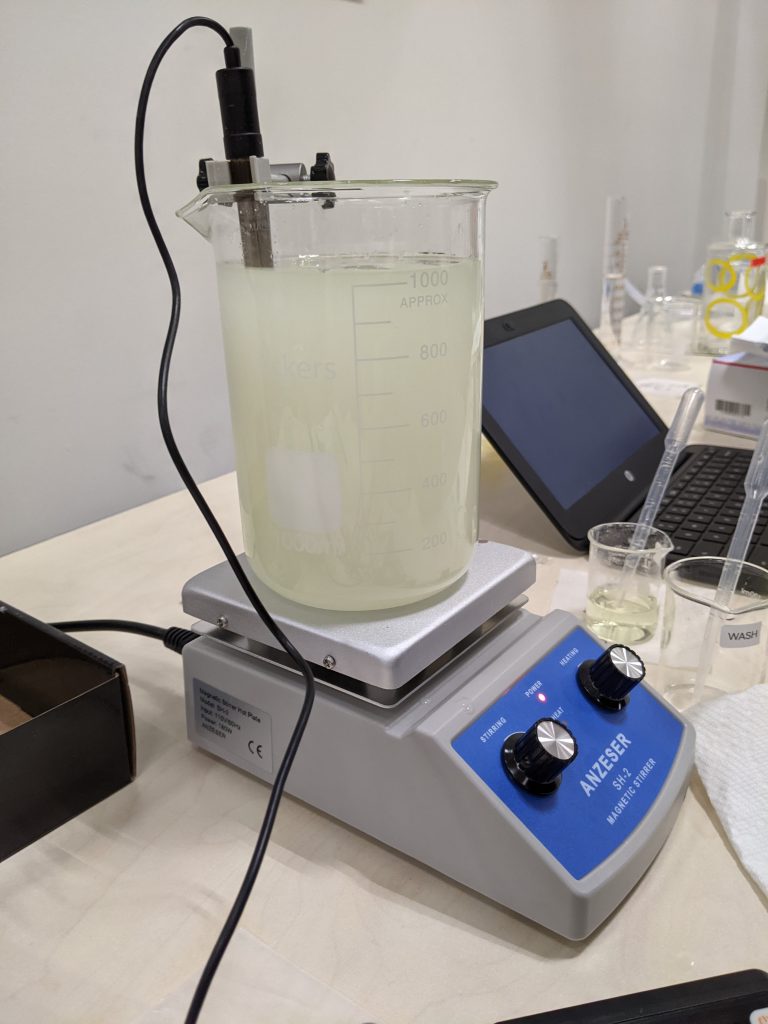

The bioplastic series is an exploratory project looking at turning cellulose into a biodegradable plastic. This was a multipart series – the first part of it was theory and we covered looking at research articles or about five key articles we covered. We then kind of built our own methodology based on those articles that we found. The general way we did that was we found what was common among the articles because they all had variations. Then we picked one of the simplest things we could do. So, we picked pre bleached cellulose. Most of the cellulose was for example from wood and wood needs to be bleached and then before it goes through our process. So, we skipped ahead, just got pre-bleached, raw crystalline cellulose. We started our project from that point forward. Then our last series was a multipart community project where we had multiple people try the project simultaneously. Ultimately, we put our plastics on a Petri dish, let it dry out and had our sample film.

What projects can attendees expect to do?

So, one of the breakout ideas was biodegradable compost bags. There was an idea to extend the series to look at whether we can layer tissue paper with our cellulose and make a glue between these paper sheets that would be strong and durable, but also biodegradable. One of the noted issues from our series is that a lot of biodegradable plastics still take 15 years to break down and at least two to three years. So, it’s not like just putting your compost in, and in four months it’s gone, they’ll still be there next year, and people were a little bit disheartened by that. So, there’s this idea: can we, for the purpose of compost bags, do something a little bit different where it’s a fast-composting process, but still biodegradable, still healthy, and still rigid for the period of time that you do need to hold your groceries? So we had a theory on one of the applications for this project where you could build your own compost bag by layering tissue paper and then our TEMPO oxidized cellulose. That’s the main ingredient that we get a wet slurry, and that’s what the chemistry gives you is this wet slurry. Then as it dries, it becomes a hard durable plastic. And our idea is to put that between two sheets of tissue paper, dry it out, and see if it becomes sturdy enough to be a bag; that was one extension. The other thing we were interested in doing was just testing the properties. A lot of our literature research kind of indicated that this would be similar properties to wood, about as strong as wood, and burns at about the same temperature as wood. So, we’d be interested in seeing for the experiments that we did. What are the physical properties? When does it stretch? When does it break? Does it melt? Does it deform under heat? Some of those mechanical properties we’re very interested in. We also talked a little bit about using dyes to see how much of the chemistry had gone forward. So, we are interested in doing a little bit of a chemical analysis as well.

What has been your highlight so far with the talk series?

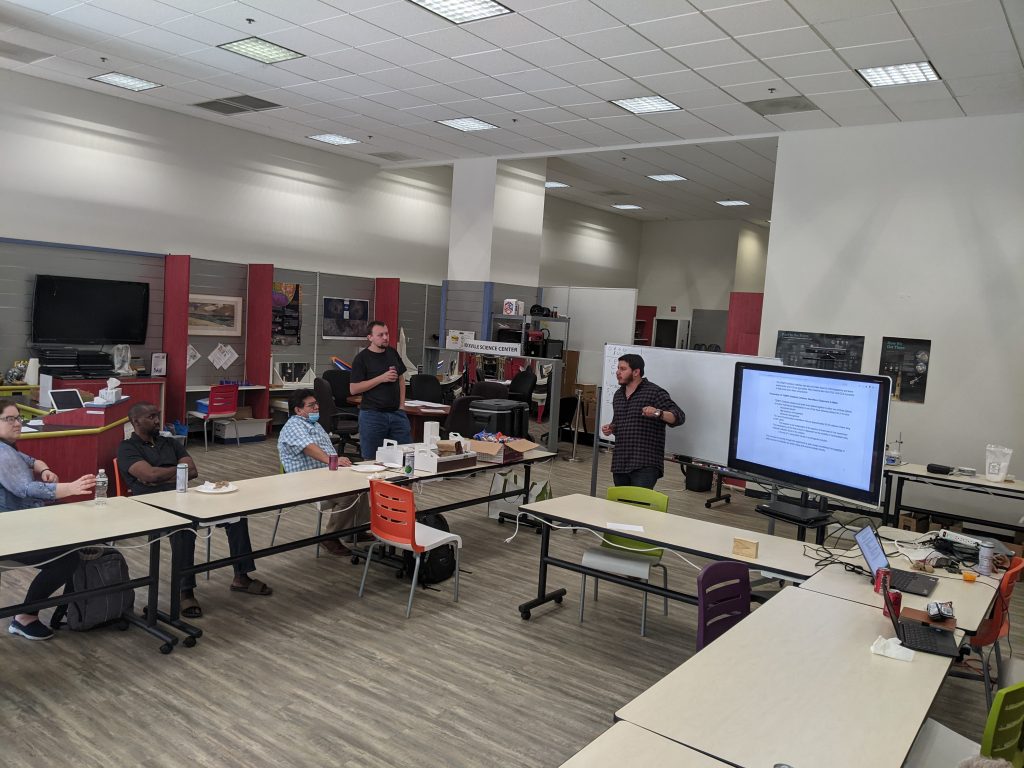

I think the best part of this talk series was really showing the community how to do a research project. I approached this like a grad student in a research lab and that wasn’t my background. I’m not doing a science PhD, but a lot of our colleagues had. In particular big kudos to Ulisses. He works at NIH, and he runs their lab there in some degree. He was able to bring a lot of laboratory experience to us and it was just really enjoyable to see what it’s like to have a theory to order ingredients to demonstrate a public experiment and to kind of show the life of a scientist in a very practical way. We didn’t know what we were gonna get, but it’s a discovery process. It’s fun, and you know, I think a lot of people enjoyed going through that journey with us. So just the fact that we could get in the life of somebody else who’s a day-to-day research scientist, I think is very enjoyable to kind of see what that would be like.

What do you hope attendees will walk away with?

I hope that attendees, walk away with an appreciation for the complexities of science. I think it’s very easy for science hobbyists to look at popular science and say it’s so easy. I read it in a journal article. It took me five minutes to read, but they kind of forget that five minute headline was probably six months of work. And a lot of failure, a lot of iteration and a lot of things that went wrong. Even in a group of 10, 15, really intellectual smart people, things go wrong. It’s the real world. So, I hope that people got out of this series, an appreciation for the journey, and the fact that it is possible to be a citizen scientist. You can do these things alone. One of the things that Ulisses and I agree on is that more institutional support for these kinds of projects would be helpful. It costs about a thousand dollars in materials to be able to run an experiment like this, and we wish that was a little bit more publicly available. But the idea that people can self-study and do their own experiments and can recreate raw science is absolutely valid. People can do that. And we really hope people get that as a takeaway message that it is in fact possible and enjoyable. And at the end of the day, you just want to make it more accessible for people and hopefully they can inspire their own citizen science journey.

I think that’s a really good takeaway. So, my last question is how can post attendees support MoCo Makers and/or get involved?

The best way to be involved is to either start a community or find a community. A lot of times you may actually be somebody who starts a community. It’s not as hard as you think. Most libraries will let you meet. It’s a legitimate way to develop a core group of members. MoCo Makers has a meetup group. We have a website mocomakers.com, meetup.com/mocomakers, and Capital Area Biospace, we were happy to partner with them. Rockville Science Center was kind enough to let us use their facilities. We don’t do what we do, especially science – we don’t do it in isolation. So, we encourage folks to reach out to other local areas, community groups, check out meetup.com, Eventbrite, Facebook events, you know, just be proactive with finding communities or starting communities of interest. It’s never been easier to star them, they’re super easy to start. The other thing is you don’t have to have a PhD to start a science group. I’m not, and a lot of our core members are not – they’re hobbyists. But all it really takes is passion. You can self-learn everything else along the way, and it’s okay to make mistakes. So, you know, we really encourage people to have fun with it and lean into the mistakes as part of the journey, be very transparent and public with it. And people will still get a lot out of it, even if your experiments fail. It’s helpful for people just to see, and just to see people going through a journey because that that’s really honestly how the world works. You have to make an attempt, you have to iterate, and you have to evolve. I think it’s just helpful for people to see that transparency. So don’t feel bad about starting something or about joining something with no experience. Almost everybody I’ve encountered has been very supportive of what we do. So, we do encourage you to reach out and look for local community organizations to join.